|

The History of Bricks and Brickmaking.

Bricks are one of the oldest known building materials dating back to 7000BC where they were first found in southern Turkey and around Jericho. The first bricks were sun dried mud bricks. Fired bricks were found to be more resistant to harsher weather conditions, which made them a much more reliable brick for use in permanent buildings, where mud bricks would not have been sufficient. Fired brick were also useful for absorbing any heat generated throughout the day, then releasing it at night

The Ancient Egyptians also used sun dried mud bricks as building materials, evidence of which can still be seen today at ruins such as Harappa Buhen and Mohenjo-daro. Paintings on the tomb walls of Thebes portray slaves mixing, tempering and carrying clay for the sun dried bricks. These bricks also consisted of a 4:2:1 ratio which enabled them to be laid more easily.

The Romans further distinguished those which had been dried by the sun and air and those bricks which were burnt in a kiln. Preferring to make their bricks in the spring, the Romans held on to their bricks for 2 years before they were used or sold. They only used clay which was whitish or red for their bricks.

Using mobile kilns, the Romans were successful in introducing kiln fired bricks to the whole of the Roman Empire. The bricks were then stamped with the mark of the legion who supervised the brick production. These bricks differed from other ancient bricks in size and shape. Roman bricks were more commonly round, square, oblong, triangular or rectangular. The kiln fired bricks were generally 1 or 2 Roman foot by 1 Roman foot, but with some larger bricks at up to 3 Roman feet. The Romans preferred this type of brick making during the first century of their civilisation and used the bricks for public and private buildings all over the empire.

The Greeks also considered perpendicular brick walls more durable than stone walls and used them for public edifices. They also realised how the modern brick was less susceptible to erosion than the old marble walls.

During the 12th century bricks were reintroduced to northern Germany from northern Italy. This created the brick gothic period which was a reduced style of Gothic architecture previously very common in northern Europe. The buildings around this time were mainly built from fired red clay bricks. Brick Gothic style buildings can be found in the Baltic countries Sweden, Denmark, Poland, Germany, Finland, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Belarus and Russia. The brick gothic period can be categorized by the lack of figural architectural sculptures which had previously been carved in stone. The Gothic figures were impossible to create out of bulky bricks at that time, but could be identified by the use of split courses of bricks in varying colours, red bricks, glazed bricks and white lime plaster. Eventually special shaped bricks were introduced which would imitate the architectural sculptures.

During the renaissance and Baroque periods, exposed brick walls became unpopular and brickwork was generally covered by plaster. Only during the mid 18th century did visible brick walls again regain some popularity.

Bricks now

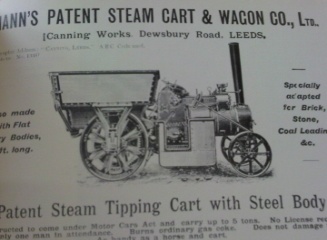

Bricks are more commonly used in the construction of buildings than any other material except wood. Brick and terracotta architecture is dominant within its field and a great industry has developed and invested in the manufacture of many different types of bricks of all shapes and colours. With modern machinery, earth moving equipment, powerful electric motors and modern tunnel kilns, making bricks has become much more productive and efficient. Bricks can be made from variety of materials the most common being clay but also calcium silicate and concrete. With clay bricks being the more popular, they are now manufactured using three processes soft mud, dry press and extruded. Also during 2007 the new ‘fly ash’ brick was created using the by-products from coal power plants.

Good quality bricks have a major advantage over stone as they are reliable, weather resistant and can tolerate acids, pollution and fire. Bricks can be made to any specification in colour, size and shape which makes bricks easier to build with than stone. Brickwork is also much cheaper than cut stone work. However there are some bricks which are more porous and therefore more susceptible to dampness when exposed to water. For best results in any construction work, the correct brick must be chosen in accordance with the job specifications.

Brick Composition

Building bricks are a mixture of clay and sand which is mixed with water to create the correct consistency. Sometimes the bricks also have added lime, ash or organic matter which speeds up the burning of the brick. The clay mixture is then formed in moulds to the desired specification ready to be dried then burnt in the kiln. Clay: The properties and quality of bricks depend on the type of clay used. The most common form of clay used for everyday bricks, is that with a sandy consistency, silicate or alumina, which usually contains small quantities of lime or iron oxide. Silica, when added to pure clay in the form of sand, prevents cracking, shrinking and warping. If there is a large proportion of sand used in the mixture the brick will be more textured and shapely. An excess of sand, however, renders the bricks too brittle and destroys cohesion. 25% of silica is said to be advantageous. Iron oxide in the clay enables the silica and alumina to fuse and adds considerably to the hardness and strength of the bricks. The iron content of the brick is evident in the colour of the brick and can be used to add the colour red into the bricks. However a clay which burns to a red colour will provide a stronger brick than clay which burns to a white or yellow brick. The lime content in a brick has two different effects. It stops the raw brick from shrinking and drying out, and it also acts as a flux during burning which causes the silica to melt and creates the bond which binds all the components of the brick together. However, too much lime can cause the brick to melt and loose shape. Any amount of quicklime within a brick is detrimental to its quality and can cause the brick to split into pieces. For the best qualities of pressed brick the clay is carefully selected both colour and composition. Clay from different sources is also often mixed together to create the desired mixture.

Manufacturing Processes

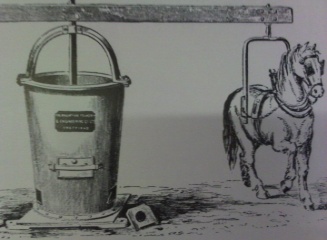

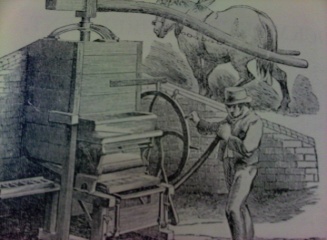

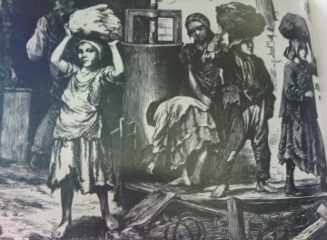

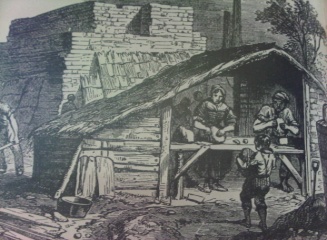

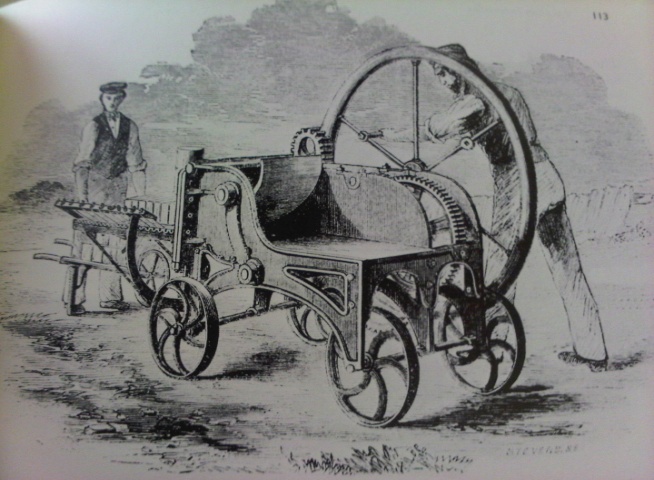

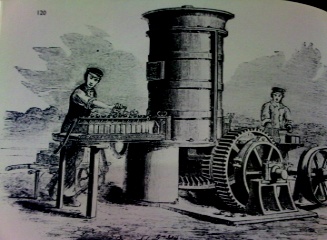

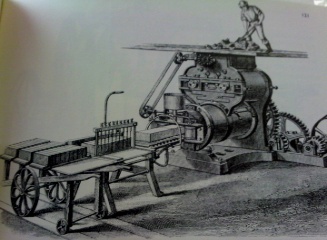

Handmade bricks used to be very commonly used throughout the UK. The process involves putting the clay, water and additives into a large pit where it is all mixed together by a tempering wheel generally still powered by horse power. Once the mixture is of the correct consistency, the clay is removed and pressed into moulds by hand. To prevent the brick from sticking to the mould, the brick is coated in either sand or water. Named ‘slop moulding’ when dipped in water and ‘sand struck’ when coated in sand. Coating the brick with sand however gives an overall better finish to the brick. Once shaped, the bricks are laid outside to dry by air and sun where they will be drying for three to four days. After this process the bricks are then transferred to the kiln for burning. If green bricks are left outside for the drying process and are left out during a shower; the water leaves an indentation of the brick is considered very undesirable. However this does not affect the strength properties of the bricks. Bricks are now more generally made by large scale manufacturing processes using machinery. This is a large scale effort and produces bricks which have been burned in patent kilns. There are three different types of manufacturing process for machine made bricks - the soft mud process, the stiff mud process and the dry clay process for which machines are specifically designed.

The ‘Soft mud ‘process is similar to that of handmade bricks. In the Soft Mud process that clay contains too much water to be extruded as the clay is left to soak in water for 24 hours. For this process three pits are usually in operation at any one time to keep the production flowing. Occasionally the clay is worked in a pug mill before being thrown into the machine. Due to the 20% water content of the clay, wooden moulds are generally used and are lined with either oil or sand to stop the clay sticking. After being drawn from the machine the filled moulds are emptied by hand and the bricks taken to the dry shed. So the soft mud bricks can be dried properly, both handmade soft mud bricks and machine made (more mass produced) bricks will both be placed in a large dryer which is separate from the extrusion dryer.

The ‘Stiff mud’ process differs because only enough water to create plasticity is added to the clay, approximately 12% water. Clay is then extruded through a ‘die’ to produce a long stream of pressed clay which is then cut to size by the machine. The die sizes and cutter wire are calculated to compensate for the shrinkage of the brick during drying and firing. Attachments can also be added to the die which gives the brick its texture from brush, roll, and scratch to roughen. Green bricks are then dried out carefully to ensure a consistent colour and strength. Because Soft Mud bricks have been created under little or no pressure, their density is not as great as that of Stiff Mud bricks. It has been argued that when Soft Mud bricks have been made and burned properly they are possibly the most durable brick. However Stiff mud bricks can have defects or planes of separation which can affect the bricks durability. However as Stiff Mud bricks are becoming increasingly cheaper to produce these are becoming the more popular.

The ‘Repressing’ of a brick is to re-shape the brick or round of any corners dependent on specification. Both types of soft mud and stiff mud bricks can be repressed when they are only partially dried. This is done by placing the bricks in metal moulds and putting them under great pressure before burning. Pressed bricks however are machine moulded bricks where the clay being used is already nearly dry. This process can make a significant difference on the appearance of the bricks. Bricks made using this process generally are more difficult to compress. Dry pressed bricks however are now commonly used for face bricks. Pressed bricks generally mean dry pressed bricks, but many face bricks are made by repressing soft mud bricks.

‘Cement’ bricks made from Portland cement, these bricks are machine moulded into size and shape to match the size of clay bricks. These are extensively used in some regions.

‘Hollow, Terracotta or Tile’. This type of product can made into practically and size or shape for any kind of use. Blocks made of terra-cotta are light and durable. For use in partitions the terra-cotta is mixed with sawdust which burns off in the kiln, but creates a more porous brick. Terra-cotta can be glazed or unglazed.

Facing Bricks Types of:-

Facing bricks are uniform in colour and shape and can now be made to any almost any specification, texture, colour and size.

Wirecut extruded bricks. For this type of brick the clay is extruded and cut by wore into individual bricks. This is a very cost effective way of producing bricks and is done by an automated production process. These bricks are readily available in a variety of styles and colours.

Stock bricks; are usually slightly more expensive than wirecut Bricks. These are a soft mud brick which are sometimes irregular in shape.

Handmade bricks; as previously discussed above, handmade bricks are very desirable and individual in shape and colour. This brick is one of the most expensive sorts of brick.

Fletton or London Brick; is a brick made from clay extracted from the south east of England which contains traces of oil which is burnt off during the burning process in the kiln.

Arch and Clinker bricks This term is used for bricks which are burned immediately. They are over burnt and sometimes distorted in shape. Body, Cherry and/or hard bricks. These bricks are of a higher quality and are generally the bricks that were in the centre of the pile of bricks which have been burned. These bricks are top bricks as they have a higher overall quality and finish. Cherry is used as a term when the clay which has been used burns red.

Salmon, Pale or Soft bricks. These are the bricks which were nearer to the outside of the kiln during burning which means they are slightly under burnt. These bricks are generally softer than the bricks taken from the centre of the kiln are therefore are of a lesser quality, although this does not affect the overall shape of the brick. These bricks are generally used for the interior of walls.

Waterstruck Brick This type of brick is a soft mud moulded brick. It uses alluvial clay which deposited at the end of the last ice age. The clay is pressed into mould lined with silicate. When the bricks are removed from their mould, they are left with a textured effect which can only be achieved using this method. This type of brick looks old and handmade even when new.

Engineering Bricks Engineering bricks are called so due to their overall strength and water absorption. The Class A brick has strength of 125N/mm² and water absorption of less than 4.5%. Class B engineering bricks have a strength greater than 75N/mm² and water absorption of less than 7%. Traditionally used in civil engineering, these bricks are also useful for damp courses and structural design.

Bullnose Bricks These special bricks are used when round edges are needed, for gate recesses, quadrants or arches.

Off Shades or Seconds or ATR or Random Quality. These are batches of bricks which are generally consistent in colour but do not match the product which is marketed.

Different uses for bricks

Dependant on their final use, the bricks are named accordingly.

Radial Bricks either have one edge shorter than the other or vary in thickness. This type of brick is used for walls with curved edges. Arch bricks are used for arches as they have one end thicker than the other.

Ordinary bricks or facebricks and have regular shape and colour used for the outside of building etc.

Fire bricks are generally yellow in colour and used in places where they would be subject to high temperatures. Paving bricks are of uniform size and colour and have been made by burning hard clay or shale. Good brick to be used where toughness and water tightness is essential. Aesthetic appearance

Bricks can be made to virtually any specification,Overall strength and water absorption of clay bricks Compressive strengths vary from 5 N/mm2 to 125N/mm2

Water absorption varies from 6-26% dependant on brick type

Brick Dimensions Metric and imperial

Brick Sizes

Metric bricks are a little smaller than the old imperial one. New bricks can be bonded into old brickwork by slightly increasing the mortar bed joint. Brick sizes have remained fairly constant over the years :-

Metric and Imperial 215 × 102.5 × 50

Standard Metric215 × 102.5 × 65

Metric 225 × 107.5 × 67

Imperial 230 × 110 × 70

Imperial 230 × 110 × 73

Imperial 230 × 110 × 76

Imperial 230 × 110 × 80

Although in the UK, the depth used to be less (about 2 ins/51mm) whereas modern bricks are about 2.5 ins/64mm.

Brick Cutting

Brick cuttingis the process of cutting bricks into the desired size or in most cases to cut and bond them together using an epoxy mortar to form angle bricks these are mainly used on bay windows and conservatories etc.

Thermal Efficiency and Compliance with Building Regulations http://www.bbacerts.co.uk/

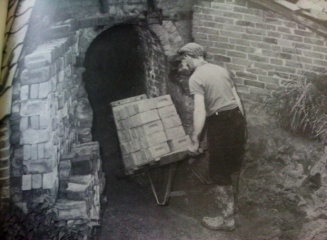

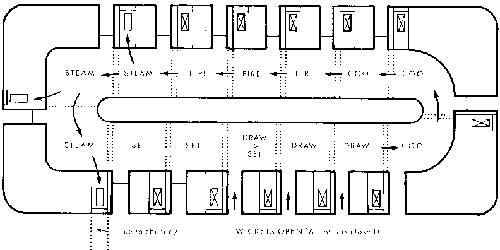

Kiln Brick Burning

After all bricks have been allowed time to dry they are placed in a kiln for burning which finishes off the brick to achieve the optimum strength and colour.

There a few different types of kilns which are currently used to burn bricks.

The Scotch Kiln is the most commonly used in the UK. This is a rectangular building which is open at the top and has side doors with fireholes built from fire bricks. The kilns will contain approximately 80, 000 bricks at full capacity. Raw bricks are arranged in the kiln leaving gaps in between each brick to ensure an even burn. It takes approximately three days to burn off the moisture from the bricks, at which point the firing is increased for the final burn. It takes between 48 and 60 hours to completely burn a brick to achieve its maximum strength. As mentioned before the bricks from the centre of kiln will be of the highest quality whilst the ones from the edges are sometimes clinkered and unsuitable for exterior work.

Up Draft Kiln. Used more frequently for handmade bricks and in small brick yards, this old fashioned kiln is only up to 15 feet high.

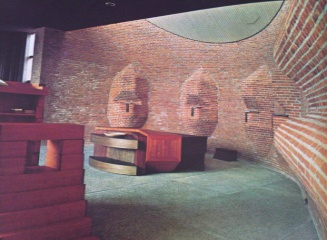

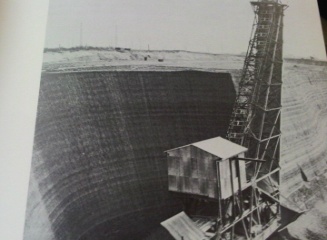

Down Draft Kilns are generally of a beehive type shape with fire produced outside of the kiln and carried in through flues. It is believed that all types of clay whether it be pottery or brick work, burn more evenly in a down draft kiln. For Terra-cotta brickwork this type of kiln is usually used.

Continuous kilns are the most expensive type of kiln to construct. This type of kiln is a continuously fired tunnel in which the bricks pass through very slowly on a rail to achieve a consistently durable brick. This is continuous conveyor belt with bricks being dried and added at one end while at the other end they are being burnt. This is a very efficient way of burning bricks. They also achieve a greater number of grade 1 bricks using this method.

The colour of brick is influenced by the chemical and mineral content of the mixture but also how high the temperature was during burning. Bricks are generally red, but an increase in temperature can change them to dark red, purple, brown or grey. Bricks containing silicate depend on the colourant used. The colour and place of manufacture is reflected in the brick names.

Mortars

To make any kind of brick work complete it must be plied together with mortar. The way in which the bricks are bonded together is vital to the strength of the overall structure. Concrete mortars contain aggregates of more than 5mm where as mortar contains aggregates less than 5mm.

General purpose mortar contains either

Sand, lime and cement

Sand and masonry cement

Sand, cement and plasticiser

Mortar is then graded between 1 and 5 depending on strength. 5 being the weakest.

Mortar Cement-Lime-Sand Cement- Sand Cement – Sand-plasticiser

The mixture has to be mixed together with clean water before it is ready to use

Normal bricks should be laid on a bed of mortar at least 3/16" and no more than 3/8" thick. For a course of bricks 8 courses high, your mortar should not exceed 2" in total. With pressed bricks being smoother a mortar joint of 1/8" can be used. For rough stone work a mortar with rough sand can be used, but for pressed brickwork it must be very fine sand.

Lime Mortar

Slaked lime is used to make lime mortar. The mortar is made by mixing sand with slaked lime at the proportion of 1 part lime to 5 parts sand. There are two types of lime used in lime mortars, one that sets and hardens by the reaction with the air (non-hydraulic) and one which sets by reaction to the water (hydraulic).

Non-hydraulic lime is made from pure calcium carbonate, or chalk or limestone. This is burned in a kiln to create calcium oxide or quicklime. When this is slaked with water it takes on another form as calcium hydroxide. Calcium hydroxide reacts with the air to set. This is what sets the brickwork together and creates the strength.

Hydraulic Limes. Calcium carbonates naturally occur but can include some impurities. It is these impurities which when burned in a kiln create the calcium silicates or aluminates that react with water to set. Enough water is added to the mixture to create calcium hydroxide powder form. The hydraulic lime is then graded depending on their overall set strength.

White and Coloured Mortar

White and coloured mortars should be made using lime putty and screened sand. Colour is created by adding additional minerals to the white mortar. Coloured mortars are not as strong as white mortars. However the more popular mortar colours are red, brown, buff and black, green, purple and grey.

Cement Mortars

Cement mortars should be used in areas of damp or below grade work, also in places which will have heavy loads such as arches. Cement mortars should also be used for setting coping stones or where the brick work will be exposed to the elements. For under water construction Portland cement mortars should be used.

Mortar Tinting from Bricks UK available at http://www.extensionmatch.co.uk/motartinting.html

When new extensions or refurbished brick and stonework are being carried out, matching the mortar joint with the original brick work can be a problem. Extension Match colour tinting extends to mortar tinting. We can match mortar colours perfectly and permanently and all work is guaranteed for the life of the brickwork.

Grout can also be tinted. Shown below is a tiled bathroom floor - the customer was not happy with the original grout finish so we tinted the grout joint which transformed the overall appearance of the tiled floor.

For example

Brick Tinting from Bricks UK available at http://www.extensionmatch.co.uk/motartinting.html Brick tinting has been used for decades by brick and masonry manufacturers and also by many developers on new house sites when there are problems between different batches of manufactured bricks, delivered on site which causes slight shade and colour differences between one lorry load of bricks and another. Tinting is then used to match the affected bricks to the colour of the original bricks, seamlessly blending the different batches together. Brick tinters do not "paint" the brick with pre-set coloured paints, the process is a chemical and oxide solution involving various colour dyes. Each match is unique and the dye is mixed on site by our specialists once they have assessed the required colours to match, including and varying blends.Matching and creating the colour on site ensures that we get the exact colour dye solution to match your individual brick in your individual situation.

The solutions change the produced colour of the brick, it is not a paint simply applied to the face of the brick, it will naturally whether just as the normal brick would, mature over the years. All work is fully guaranteed for the life of the brick.

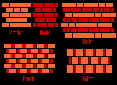

Brickwork Bonds

Brickwork bonding is how the bricks are arranged. They usually overlap in between courses which helps distribute the load and provide a more stable structure. General brickwork should not be less than ¼ bonded with mortar.

Stretcher bond

This bond is the most commonly used today. Bricks used to make this bond are just half a

brick wide. As with any brickwork, no two adjacent vertical joints should be in line. When

turning a corner at the end of straight run, the two runs should be interlocked on every other

course.

English Bond

An English bond has alternating courses of headers and stretchers. The alternative headers

should be centred over and under the vertical joints.

Flemish Bond

This bond has alternating headers and stretchers along each course. The headers should be

centred above the stretchers above and below.

American Common Bond

This bond is very similar to the English Bond but its headers run one in every six courses of

stretchers.

Header Bond

This type of bond is used for walls which need to be curved. It is made by full bricks laid

header wise with a ¾ bat on alternate courses.

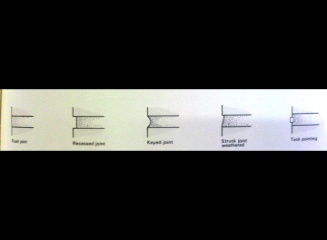

Pointing

Pointing is effectively the application and maintenance of the mortar which bonds the brickwork. After the masonry has been laid, the gaps are in filled with mortar, this is known as pointing. Pointing should not be done during any extreme hot or cold weather.

If re-pointing, any vegetation growing on the mortar should be removed and the existing mortar should be chiselled back. This should be done using either s plugging chisel, club hammer or mini angle grinder to a depth of 13mm.

All the debris should then be washed off and the walls should be left to dry before the re-pointing begins. The mortar used for the pointing should be 1 : 3 parts and be quite stiff so the mixture does not fall of the trowel.

Different types of Pointing

Weather Struck Joint

Weather Struck and Cut Pointing

Similar to the previous weather struck joint, except the bed joints are neatly trimmed using a Frenchman or pointing trowel.

Tooled, Bucket Handel Joint

The most popular joint used today, where the joint bed is slightly rounded inwards. The mortar should not be pressed in too hard. The tool needed for this job is a rubber hose, an old type bucket handle.

Flush or Rag Joint

This finish of this joint is flush with the brick work, smoothed off with a rag. This finish should only be used for brickwork above water level.

Recessed Joints

This Finish of this joint is recessed. The mortar is formed to a consistence depth of approximately 5 mm. This joint should only be used with a frost resistant brick and is not recommended where the brickwork could be exposed to severe wind driven rain.

This type of joint should be used when the bricks have become uneven over time due to weathering. The joint is pointed by filling the perp joint first and then the bed joint which would be shaped by placing the trowel on the perp joint and angling it downwards to create a smooth finish.

With thanks to www.expressbrick.com

|